The Elusive "True Preference": Do You Really Know What You Want?

In last week’s article, we described what is a good schedule from a unit perspective, and why is it so challenging to create one.

Today we’ll focus on the individual, and show how difficult it is to us as humans, to discover and describe our true preferences, in general, and related to our next schedule.

Imagine Sarah, a busy nurse, struggling once again to fill out her shift preferences for an upcoming schedule. With two young kids, she’s constantly juggling childcare, school, and last-minute changes. She also has to consider her spouse’s work, social events, appointments, and her own need to rest. Every shift she chooses affects her entire family and personal life. Planning 4 to 10 weeks ahead feels overwhelming, so she often defaults to her regular shifts with the occasional day off, instead of truly aligning her schedule with her complex life.

It’s not Sarah's fault, this is just how are brains are wired. Thinking about thinking. . . it’s a crucial first step before we dive in with a technological solution about how to ‘fix’ or ‘improve’ the way we do things. Not just for the nurse scheduling problem, but before we implement any type of technology.

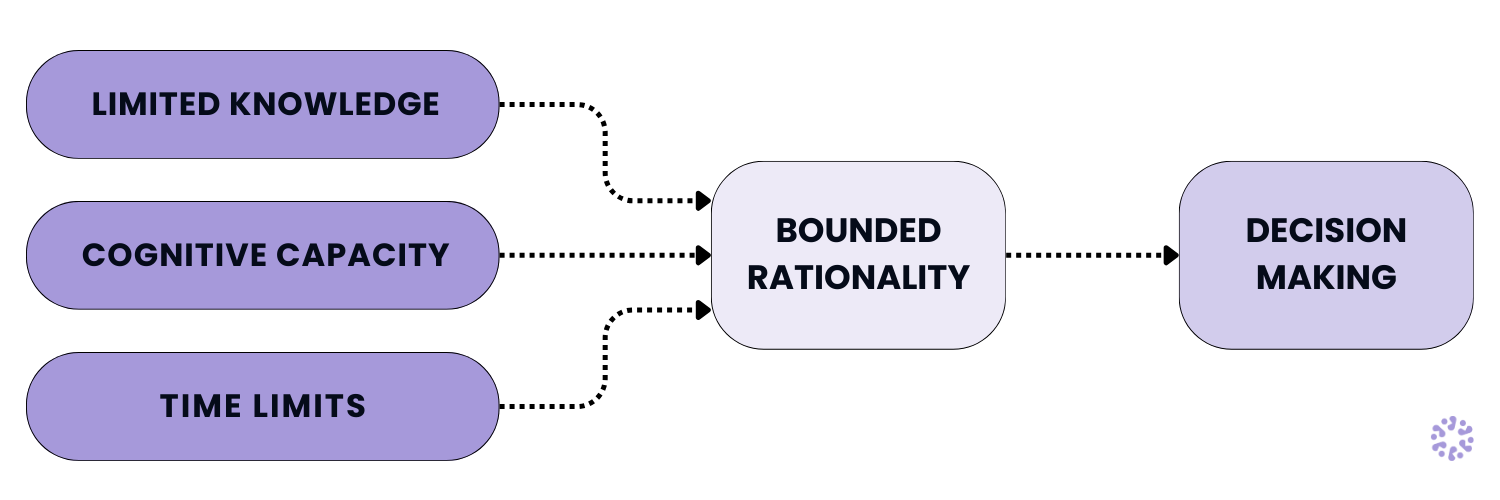

Bounded Rationality: The Limits of Our Cognitive Power

The concept of bounded rationality, introduced by Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon explains why we often satisfice, accepting a “good enough” solution, rather than optimizing. It suggests that our rationality is limited by the information we have, the cognitive limitations of our minds, and the finite amount of time we have to make a decision. Whoa - that’s deep. . . in other words - as Sarah knows, there’s only so much time she has to think about her schedule, so she usually settles for less than the ideal.

In the context of self-scheduling, nurses are operating under these limitations. They don't have time, capacity or a crystal ball to tell them the perfect information about all possible shift combinations. Like most of us, their thinking power is tied up with solving day to day problems, and they have limited time to spend thinking about the future. Expecting Sarah to know and choose the best possible schedule, weeks ahead of time is not only unrealistic, It’s really not possible.

In the same way, a charge nurse who’s solving the nurse staffing problem, when creating an upcoming schedule can’t really think through all of the possible combinations. We are humans, not robots.

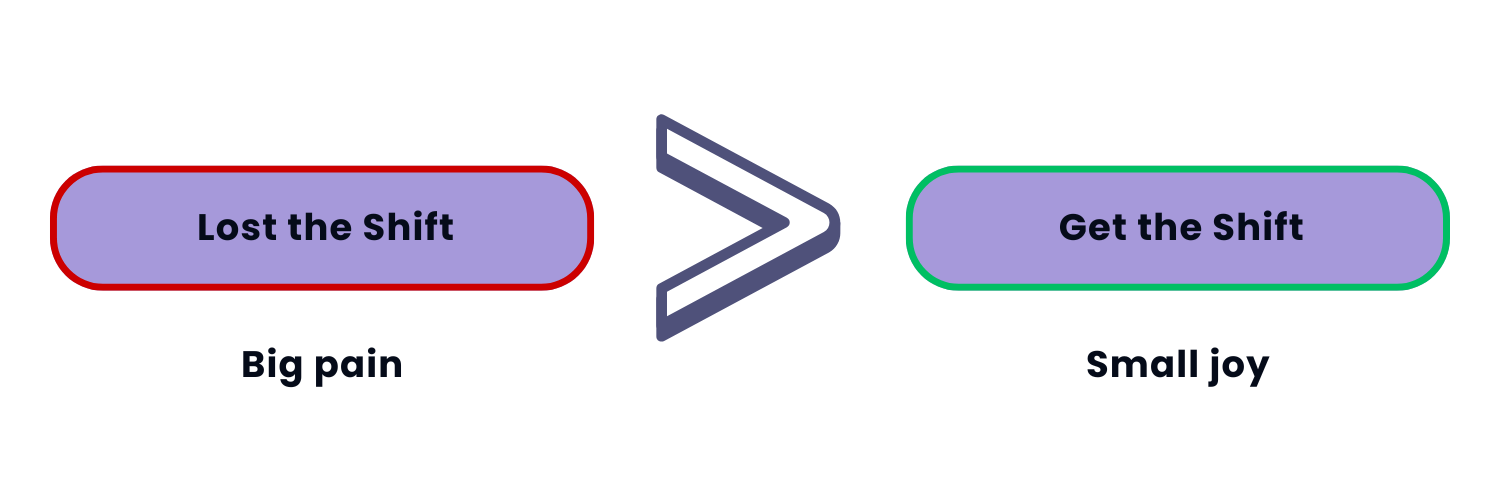

Loss Aversion: The Pain of Giving Up

Another powerful psychological factor making it hard to reveal true preferences is loss aversion. This cognitive bias describes our tendency to feel the pain of a loss much more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. In simple terms, we'd rather avoid losing something we already have than gaining something new of equal value.

In self-scheduling, this means staff members often feel the perceived loss of shifts they wanted but didn't get far more acutely than the gain of good shifts they were assigned. Even if the overall schedule is beneficial, missing out on a highly desired shift can create disproportionate negative feelings.

Sarah experiences this when she requests to swap out of her normal shift rotations. What if the patient load is worse on M/T instead of W/Th that week? Swapping shifts means she won’t work with her favorite team, and she’ll miss out on the juicy updates.

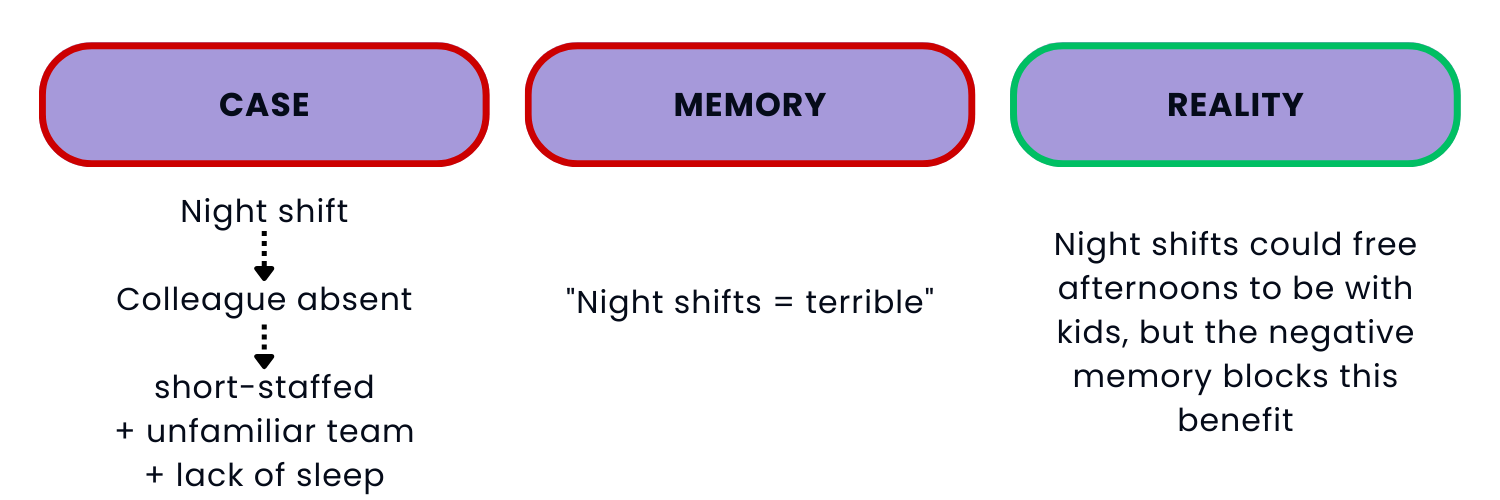

Availability Heuristic: The Influence of Easy-to-Recall Information

Another cognitive shortcut affecting true preference is the availability heuristic. We overestimate the importance of events that are easy to recall, often swayed by recent or vivid memories.

When a nurse has a difficult shift, it can form a lasting negative impression. This negative memory can heavily influence future preferences. They might then strongly avoid that specific shift type, co-worker, or even a particular patient - even if such difficult shifts are rare, or if other patterns offer greater benefits.

Sarah recently picked up a night shift. The nursing assistant called in sick, so she had to work short-staffed, with an unfamiliar team, not to mention, short of sleep! This recent, easily recalled experience has her avoiding all night shifts for a while. Even though she’d prefer to be home to greet her kids after school, and night shifts would work better for her family schedule. Her experience overshadows a balanced assessment of her other needs, which means, when you ask about her true preference, you don’t really get a true answer.

Unlocking True Preferences: Strategies for Better Self-Scheduling

Understanding these psychological aspects is crucial for designing effective self-scheduling systems. Simply asking people what they want isn't enough; we need methods that bypass our cognitive shortcuts and biases to reveal a more accurate picture of our desires.

Academics who study human decision making have developed methods to bridge the gap between stated and true preferences:

- Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): This is a method that helps people make tough decisions by breaking them into smaller, easier steps. Start with the big questions - prefer Day shifts or Night shifts, and then drill down to the smaller fine-tune questions - prefer to work with Juile or Tom. Looking at all the answers together creates a clear picture of overall preferences

- Law of Comparative Judgment: This approach also uses a series of questions, but focuses on simple, pairwise choices. For example: “Do you prefer the Wednesday morning shift with Sally, or the Thursday night shift?” After answering enough of these comparisons, we can build a very effective schedule based on true preferences.

- Gamification: Transform the shift-selection process into a fun, engaging game. Replace the old, boring system of picking shifts with an interactive experience full of jokes, surprises, and prizes. By making scheduling playful, staff are more likely to reveal their true preferences while enjoying the process, increasing both engagement and accuracy.

That’s all great in theory, but what do we do now? Sarah can’t participate in a scientific study every time she submits a schedule, and we really want to give her a better scheduling experience. That’s where technology comes in. The right tools can remove the burden, filter out the noise, and let both staff and schedulers focus on the decisions that really matter. Stay tuned for our next set of blogs to discover how we can improve Sarah’s schedule without making her life any harder.

%20(6).png)

%20(2).png)

.png)